Roger Brown was one of the leading painters amongst a group of

artists whom we have come to know as the ‘Chicago Imagists’. Art history likes –isms and –ists

because its students are more comfortable with compartmentalising species

rather than comparing the divergent characteristics of individuals. From many

of the various readings, it seems the artists of this period in Chicago were

uncomfortable with a strict collective definition but it has stuck and it does

no harm; a little like ‘outsider art’; a concept which is globally fashionable

but which also doesn’t need any more description than what it is: simply ‘art’.

When artists are friends, exhibit together and make complementary works, it can

oftentimes give the impression of a shared movement of artistic intent, rather

than a common source to each individual’s imagery. Sometimes it is simply a

very talented group of individuals who have been lumped together by chance,

fashion or convention.

Roger Brown in his studio. Courtesy of the Roger Brown Study Collection. Visit the website here

Brown was a regular member of joint-exhibitions and surveys

whose thrust and often even names perpetuated a group vibe. Whether Brown and

his colleagues were part of a group or not is not of primary importance today;

many of the artists are important in their own right and have recently been

enjoying surveys and important solo shows. Ultimately, the artists of Chicago

from 1966 to now were and are artists with highly individual energies. Their

geographical proximity and shared rejection of the prevailing trends in

American art at the time bound them more than anything else except perhaps a

sense of fun and respect for the supremacy of surface and image over concept.

Nonetheless, Roger Brown was and remains one of the most

individual voices in American painting. Despite this statement, he was an

artist whose imagery benefited from many sources. Identifying these has become

as much fun for art historians and students as quoting them clearly was for the

artist in the studio. Whilst it is enjoyable (though exhausting) to pick where

Brown’s individual works may have drawn from Georgia O’Keeffe, Arthur Dove,

Sienese painting, the work of Joseph Yoakum, Giorgio De Chirico, primitive

sculpture, southern folk art, etc. etc, it is his political and social

commentary as much as his pictorial ingenuity that commands attention and which

is the loose focus of the present exhibition.

Roger Brown died before his time in 1997, and whilst other

artists from the period have enjoyed careers that have, along with their lives,

endured, Brown’s politics within the work has at times existed in a

conservative climate. Many paintings in the oeuvre of Roger Brown explore the

politics of sexuality, homosexuality and the cultural stigma that was attached

to the AIDS virus, which ultimately claimed his life, in America in the 1980s

and 1990s.

To find a path towards the discussion of Brown’s sexual

politics, it is important to traverse his visual landscape. Here, an assessment

of the skyscraper works will serve as a backdrop for commentary on some of the

contentious aspects of his practice.

To know what a Roger Brown painting looks like is to be

expected of someone familiar with the work of the ‘Imagists’. Brown’s Land

of Lincoln (1978) adorned the jacket cover of Who

Chicago? the accompanying publication to the

important exhibition of the same name that toured England in 1981. This is

perhaps the most important contemporary book that banded and branded the

‘Imagists’. As for his imagery throughout a career, Brown is a good deal more

than a painter of tall buildings, although these have been the works often

chosen to illustrate him in surveys or articles, are the most sought after

commercially and have become the regular mental images of what his work ‘is’ or

‘looks like’ over the years.

Brown possessed an accomplished and distinctive style. He

enjoyed a command over composition that allowed for the successful execution of

large canvasses with uncomplicated motifs, oftentimes repeating them with a

rhythmic nature that was never monotonous. For instance, there is a musical

quality to a work such as Buttermilk Sky

(1974) with its repeating hills, shrubs and clouds that is kept lively by its

various punctuations; a rearing horse, a campervan, a hitchhiker. A similar

detail in Virtual Still Life # 22, the airplane is another of

these punctuations but this time an intended, subtle distraction. Within

small offerings such as these, unfurl

narratives that are neither obvious nor meaningless. Thus, curiosity and

voyeurism become central to Brown’s narrative. It is rare that the viewer is

fully aware of the story behind a work’s image unless it is one attached to

fact, as in one of his ‘history paintings’, for instance Assassination

Crucifix (1975).

Roger Brown, Virtual Still Life # 22: Service with a Smile, 1996, Private Collection

Voyeurism is inherent in the architectural paintings. It is

undeniable that Brown’s most famous works depict buildings. If these are his

standout subjects, then their windows populated by stylized silhouettes are an

important hallmark of his work. It was visiting the Roger Brown Study

Collection in Chicago that I realized one aspect of why I had always taken to

his work with joy. As a child, I had played with a vintage Dick Tracy tin squad

car. The siren whirred as the wheels moved and on the side, front and rear

windows, yellow squares framed the front, side and back depictions of the faces

of Dick and the other officers in the car. Getting close up to some of the

works in the 2012 exhibition, Roger Brown: This Boy’s Own

Story gave me the first opportunity to see the activities

of the figures so often lost in images of the works from books.

The windows of the Hancock

Building (1974) depict on one side of the

sculpture such innocuous scenes as a group dancing, a man being admonished by a

woman and a sole woman waving, whilst the

next side depicts several floors of raucous sexual activity playing out.

Compare this to the sculpture in the McClain collection (now in the Madison

Museum of Contemporary Art, Wisconsin), Skyscraper

Pyramid (1974) and that seems an altogether better

behaved address. Then again, in Me’s Building Highrise (1972) an entire lewd liason from anonymous meeting in the

park to post-coital smoking seems to play out in a simultaneous depiction for

one lucky couple on every floor of a strikingly similar building to the McClain

pyramid.

Roger Brown, Hancock Building, 1974, Roger Brown Study Collection,

the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Visit the website here

Identifying Brown’s regularly appearing characters: the woman

with her hair elaborately coiffed, the

young man with his peaked at the front

for example, is not of urgent necessity. If desperate to find identity, the

publication Roger Brown: Southern Exposure bears two helpful images that the viewer may use to make up

their mind: one is a self-portrait sketch c. 1960 whereby the hair on the youth

mirrors that which recurs in the windows on the young figure. A second image depicts

a photograph from the mid-1940s of his parents at the beach, where his mother

wears her hair very similarly to the recurring woman (usually standing

shocked). Neither hairstyle was remarkably rare for the era and reading too

much into this, whilst tempting, serves no real purpose. Whilst art is arguably

inherently autobiographical, Brown’s was about conveying the mood of the time.

These paintings were as much about sexual liberation or repression in general,

as about Brown’s own.

Identities and activities of the occupants aside, whether the

architecture paintings became synonymous with the style of Brown because they

were the strongest compositionally or that they assisted the placement of

‘Imagism’ in geographical terms is unclear. In an essay in the publication Art

in Chicago: 1945-1995 prepared for an exhibition of the same

name at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago in 1996, Judith Russi Kirshner

states “Brown positioned himself in his artwork as an anti-authoritarian

outsider” and that he “anthropomorphized the city’s modern skyscrapers and

paradoxically became the standard bearer for Chicago Imagism”. Kirschner also weighs the suggestion put

forward by Mary Gedo that the architectural works relate biographically to his

“positive alliance” with architect George Veronda, (1940-1984) whom Brown began

a relationship with in 1972.

Notwithstanding artistic motive, which likely varied from work

to work, the city/building works are laced with wit, much like the modernist

and post modernist architecture of the city. An industry flourishes along the

river through Chicago with countless amusing but conflicting stories relating

to the inspirations behind or architectural theories surrounding the buildings

across the city, as told by the guides

on the river cruises that go up and down ad

nauseum. Possibly none of the architectural works

holds as much inherent humour as Post-Modern Res/Erection

with Observation Deck (1984). Attached to this work is the

most obvious notion of the attachment of ego to the size of one’s erection,

architectural or otherwise. There is nothing subtle about the fact that even

though Chicago’s John Hancock Centre is 25 meters taller than the Chrysler

Building in New York, it is still 37 meters shorter than The Empire State Building.

When ,in 1972, the first World Trade Centre soared at 417 meters it would take

until the Sears Tower in Chicago was finally erected in 1974 at 442 meters

before people could rest assured of their superiority in Chicago. Little

articulation about the phallic connotations and the superiority/inferiority

dilemma therein associated is really required. Remember, Hancock

Centre was illustrated in Who Chicago as ‘Big

John’.

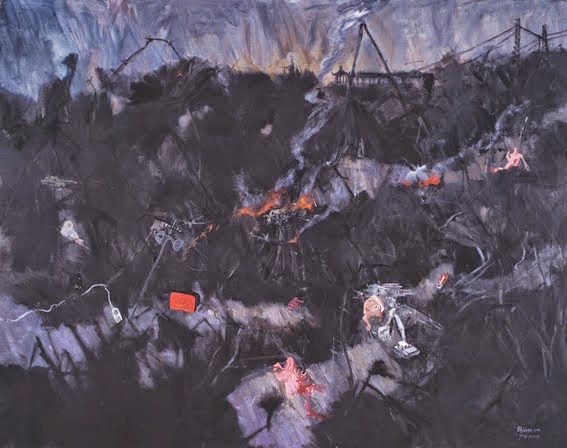

On a somber note, it is worth examining a number of works in a

very different light, to put into the literature on his painting an interesting

observation that followed his life. Brown, as will be discussed further below,

was conscious of social and political events and often depicted them. Dying in

1997, Brown missed the earthmoving events of September 11, 2001, their

aftermath and the visuals that the world was met with. One cannot help but

consider Twin Towers (1977),

the sculpture in the SAIC’s New Buffalo collection against the backdrop of

preceding works such as Ablaze and Ajar (1972) in the Museum of Contemporary Art Collection, Tropical

Storm (1972) and Midnight

Tremor (1972). It is disturbing but difficult

not to compare the grim imagery of the falling figures depicted in the

canvases, tumbling, arms outstretched from the buildings whilst they crumble

and breaks apart, to those photographs that few can forget of the victims

falling to their deaths from great height before the twin towers came down.

Brown, who never made an image flippantly seems, with a work such as Ablaze

and Ajar to be portending something about the

march of society, or the pace and peril of modern life. Within this frame,

these works lose all their humour and adopt enormous power. Such is the

strength of the period’s motif.

Roger Brown, Ablaze and Ajar, 1972, collection of the Museum of Contemporary Art,

Chicago. Visit the website here

There is probably little doubt as to the side of politics

Brown might have fallen on as dictated by his art alone. The imagery of his

political discourse is fairly liberal and the wit with which it is portrayed

has the hallmarks of that thoughtful, amusing style of political commentary

Australian audiences might associate with the pages of the New

Yorker. This is not a strictly speaking

‘Democratic’ viewpoint, but at least a thoughtful one. His outlook might at

once loathe most of the politics of Reaganism but adore the charm, bravado and

at times self-parodying nature of the Reagans themselves. The present

exhibition, His American Icons draws specifically on Presidential

Portrait (1986). This work, now in a private

collection in Sydney, is a classic piece. It puzzles me that it has hitherto

remained unsold in the estate. Included in the 1987 retrospective of Brown’s

work at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, and illustrated on p. 80 of

the catalogue, it is one of the great directly political works in his output.

It could be advanced that the subject had posed a problem with his otherwise

Democratic audiences in liberal Chicago and New York.

The irony so successfully portrayed by an artist who owned a

novelty pair of Reagan slippers is the crucial aspect to the work. Irony is a

central theme in the political works: Brown was not in the business of jamming

tough medicine down the throat of his audience; his was a point that was best

delivered with cutting but amusing elegance. Much like a joke at someone’s

expense, his political works are laced with enough humour to provoke either

hearty amusement or at least nervous laughter, often both when successful. Presidential

Portrait does speak about American icons. Politics

is polarizing. The simple image of Obama’s Hope campaign from the 2008 election raises both pride and ire

depending on the audience. How dearly we might long to see how Brown, the most

visually communicative and specific artists of his day might have commented on

the characterization of America now: how would Brown record the election of

Obama or document the Gifford Assasination attempt or the tragedy of the Sandy

Hook Elementary School shooting? One particular event in the United States that

Brown should have been able to depict upon his canvas was that important court

ruling in 2013 when the US Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional, the

key section of the Defence of Marriage Act (DOMA), passed by the Clinton

administration (who would later advocate its repeal) a year before Brown’s

death . The most enduring image from this episode was Jack Hunter’s cover of

The New Yorker depicting the Sesame Street ‘friends’ Bert and Ernie watching

the ruling on their television.

Writers are careful with the sensitive nature of Brown’s

ultimate demise. However, one should be disinclined to remain too politely

silent about what invariably, the man who painted Aha!

Heterosexuals Fuck Too (1991) clearly wanted debated. Attitudes

towards both heterosexual and homosexual victims of HIV and AIDS remain varied.

Aha! is a powerful work dealing with how

‘civilized’ America was supposed to deal with the iconic Magic Johnson

suffering from the ‘gay’ disease. Stigma has haunted this virus and it

continues to do so. More and more education, prevention and better treatment is

changing this perception, however it has some way to go. That said, as with the

newly unconstitutional nature of DOMA, and more nations legalizing same sex

marriages, attitudes are changing; something that Brown had begun discussing

many years ago. His works today are important pioneering images at the

beginning of that arduous path.

Roger Brown, Aha! Heterosexuals Fuck Too, 1991, Roger Brown Estate

Painting Collection, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Visit the website here

Roger Brown painted sharp, idiosyncratic paintings and made

sculptures that challenged and played with the conventions of the boundary

between fine sculpture, low object and also painting itself. From the earliest

canvases in the current show, the theatre images, to the California

Gawkers painted in the final year of his life,

he advanced his argument about how form could be non-naturalistically but

elegantly conveyed on a canvas. There is much to be said about the importance

of Roger Brown’s subject matter, and throughout the oeuvre it calls for fun as well

as serious considerations. The most powerful of Brown’s works interlace irony

with his desired message; they use a playful gesture or narrative to convey his

statements.

EH

Copyright © Evan E Hughes

Roger Brown, California Gawkers, 1997, Roger Brown Study Collection,

he School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Visit the website here

EH

Copyright © Evan E Hughes