Beauty is a conundrum. There are beautiful things and there

are images of beautiful things. There are visual idealisations of imperfect

things and imperfect renderings of otherwise splendid things. What is it that

makes a rotting piece of fruit less beautiful than a fresh and ripe one? Is it

anything at all when the likes of a seventeenth century Dutchman can render the

former in such a compelling manner so as to restore its beauty immediately?

There are numerous treaties on beauty, and yet perhaps the

difficulty in finding its definition is down to the fact that the term itself:

‘beautiful’, is used to describe the indescribable. Because one man’s Madonna

is another’s Medusa, and vice versa, the definition of beautiful will differ

infinitely, from each beholder to the next. Therefore it is not overly

precarious to define beauty along the terms of the compelling. You find

yourself drawn into someone, or something, you cannot describe it, you are

compelled. You find that person or object, beautiful. In many ways if one

follows this line, the concept of what it is to be ‘beautiful’ is

interchangeable with that of ‘shocking’.

Consider the rotting fruit again; when depicted in layered

oil glazes by for instance a de Heem or a Breughel, the lustre of the fruit,

slick with its sheen of emanating juice, draws the eye immediately. And yet, is

this because the subject itself is beautiful, or rather because there is an

element in human nature that is particularly drawn to, if not the evidence, at

least the notion of death and decay?

Jan Davidsz de Heem, Still-life with Fruit and Butterflies, National Gallery of Canada

Explore the collection here

I think of the Cubists when I think of Yang Jinsong’s

paintings, as do I think of the Dutch still-life painters I mentioned earlier,

An artist such a Pieter Claesz had only but to depict a rich open pie, golden

crusted, filled with fruits, meat and nuts perched next to a beautifully curved

knife at its opening to speak volumes about the comfortable wealth of the

Netherlands in his era. In doing so he could also speak of an opulence, which

was at once unbecoming for a nation whose supposed puritan values would have

had them be more modest. He was not moralising but rather merely remarking, he

most probably enjoyed consuming the beautiful objects he depicted as much as he

did creating the images of them. Another great source of wealth, though also a

vice, which was included by Claesz and others was the depiction of tobacco and

the paraphernalia of smoking. Often there would be a conical wrap of

printed paper, out of which spilled the evidence of tobacco. A pipe might be in

the background and the thinnest wisp of smoke lingering above the composition.

The inclusion of the vice certainly hints briefly towards sin, but also speaks

in terms of the impermanence of life. The fleeting nature of smoke that is here

one minute, lingers and then is gone. Jinsong’s paintings also include these

symbols of sin. Jinsong’s fish are at times scattered with syringes or pills.

Now, if one things of the Tobacco which was famously traded out of the Dutch

East Indies, and then considers the volumes of opiates, mainly heroin produced

in the border regions of China, indeed a narcotic itself which was for many

years through the 1970’s and 1980s called ‘China White’, one observes a very

tidy link.

Pieter Claesz, Still-Life, 1636, Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Explore the collection here

Now Picasso and co. they liked Absinthe. They liked young,

beautiful, loud prostitutes and they loved to consume fabulous bottles of wine.

The café collages and cubists musings of the 1910-1920 years tell us as much.

So much preoccupation can peak only of the voluminous understanding of how much

fun they could have. That is not to say they didn’t know these excesses were

bad for them. Then again, Picasso did not moralise, in the entire canon of

literature on him, no one would level that accusation at a man, one of whose

earliest famed works is a self-portrait as a late teen being administered

fallatio by a Spanish prostitute. I cannot accuse Jinsong of moralising, his

paintings don’t they comment without prejudice, though they staunchly fail to

deny the ugliness around us.

Picasso, Pipe, Glass, Bottle of Vieux Marc, 1914, The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation,

Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. Explore the collection here

Yang Jinsong’s paintings over the last five years have been

a discourse on human behaviour, and of beauty. Yang Jinsong’s fish paintings

are unquestionably beautiful. Some are grotesque in their violence, some are so

sensual in their colour and expressively laid brushstrokes that the viewer is

almost repulsed to the pint where they can smell the rotten flesh of the fish

and the gag reflex is very nearly tempted. Either way, one does not eerily turn

away from these paintings. There is something about fish itself that is

extremely provocative. The protein has the tendency to completely polarise

people, one is either a fish eater, or staunchly not, some will only eat fish

and many others just can’t stand the smell. In Australia, where over the last

two decades at least, the procurement of fresh seafood has been a relatively

gentle challenge, we tend to be more pictorially tolerant if not inclined than

elsewhere in the world. Indeed, it is no great surprise so many of our finest

national chefs have all but made their name on the back of the freshness of the

industry here. In China, fish holds the tendency to serve as a great delicacy,

and equally become the picture of nightmares.

Yang Jinsong, private collection, Sydney

The concept of hospitality in China is a little different to

that which westerners are used to. A western businessman might ask a client to dine and think himself generous if he picks up most of the tab for a modest lunch at

the local brassiere. In China, Corporate hospitality seemingly knows no bounds.

Banquets that last hours into night are commonplace, and usually end with the

most torturous karaoke known to man in grim smoke filled rooms reeking of white

spirit. At some point along the way, at any business-oriented banquet worth its

salt in China, one or more fish will be presented. It will be proudly thrust

beneath the eyes of the guest of honour who will look down at the glassy black

eye of some recently steamed bass or two. Maybe it’s the English, with their

pedantic attention to neatness and order that the Dover Sole is perhaps the

only truly tidily deconstructed fish I can think of. As I have known it, there

is no neat way to eat or portion these live fish presentation platters at a

Chinese banquet. The fish comes to the table, everyone duly appreciates it, and

more often than not a comically intoxicated host proceeds to portion the fish

to their guests. By this usually late stage in the meal, bones, guts and whole

chilli garnishes are quite an afterthought. What is thought to be the finest

delicacy to bestow upon a guest is more often than not tiresomely difficult to

consume. The most beautiful intended part of the meal is also the most

challenging.

Yang Jinsong, private collection, Sydney

Yang Jinsong, private collection, Sydney

Yang Jinsong, private collection, Sydney

At the end of any of these Banquets, if one has survived the

rice wine, comes the fruit. The like of which I mentioned earlier, it must be

said, I have rarely experienced the limp flavourless watermelon which one can

easily find in a country where supermarkets import fruit year round from

wherever is convenient. In China, usually at rural restaurants, the melon is

amongst the sweetest and juiciest you might imagine. And yet with this

sweetness, comes the undercurrents. I have been fascinated to witness the

appearance of the coupling figures in Jinsong’s recent paintings. These

pink-fleshed girls clad in their black fishnets are up to all sorts of mischief

in and about these enormous melons (whose obvious connotations are perhaps a

little misplaced with regards to my observations of the Chinese bust). The

seedy undertones of sex are never far away from the Chinese Banquet. After the

meal, businessmen will be carted to the nearest teahouse to be entertained by

their hosts. If the host is looking to score big points he will simply have a

series of girls paraded in the restaurant (when the mood is convivial enough). This

is when the Karaoke starts. On each trip I have taken to China there has always

been at least one or two stories in the South China Morning Post or the China

Daily English newspapers about a loyal official getting himself into trouble

around about this time in the evening and a short, sharp moralizing column

ensues. Jinsong’s luscious offerings of his bursting melons, littered with

microphones and naughty nymphs, do just enough to set the scene without being

erotic, moralising or boringly pornographic.

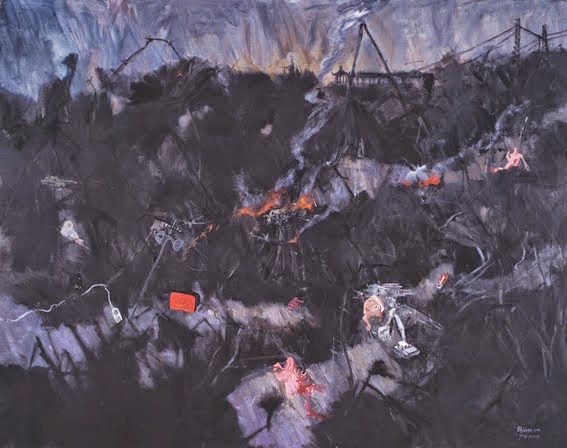

Alongside the still life painting of Yang Jinsong sit his

landscapes, He is perhaps not same painter of landscapes as he is of the

stunning food compositions, however in an exhibition such as this they play a

very important role in the literalising the themes on which eh touches in the

former paintings. An Olympic games is for its host nation very much the proud

presentation dish. They are the richest offerings of the splendour of a culture

and its progress in the world. For the most part. Or at least what was

broadcast around the world, the Beijing games were a glittering success

performed underneath miraculously clear skies (for China). The games showcased

the most architecturally remarkable arena and were a technological marvel, envy

you couldn’t access the BBC website. Perhaps these games are all too often

offered as an example of veneer over truly wonderful inner workings, at least

of the country as a whole. Jinsong’s Black Lotus’ purposely includes the

Olympic flag and the viewer starts to get the sense of what it is the darker

elements in the brighter paintings all refer to. These landscapes are bleak,

they are uninspiring and they are most certainly not beautiful. And they remind

me too clearly for the drive, which I have taken a number of times between the

cities of Beijing and Tianjin. These dark paintings are stark reminders of a

darkness, which lurks in modern China, but of course not just China, but

anywhere. I spoke earlier of glorious colourful de Heem paintings or of the

boisterous vices of the cubists. The drive between Beijing and Tianjin is quite

beautiful compared to those grim railway stations in the industrial ghettos

around Rotterdam or the grey concrete outskirts of Paris. There is light, and

there is darkness. It is not a Chinese thing, but very much a modern thing.

Yang Jinsong, private collection, Sydney

EH

Copyright © Evan E. Hughes, 2014

No comments:

Post a Comment